“We always think we’ve created the ‘ultimate’ model of the universe, and then something new comes along that changes everything. It’s simply a continuous pattern in humanity’s unstoppable march forward. We have to get used to that idea, and finally become more humble.” Stock Clash Picture

Its cute and sparkling shape fills your computer screen with light. Our online meeting started via zoom, and American physicist, journalist and author Marsha Bartosak is ready to talk about what makes her latest book, “The Day We Discovered the Universe” (Torpe Publishing, 2022) so exciting. A book as ambitious in scope as the science epic it narrates: an astronomical investigation that took place at the beginning of the twentieth century and led to the terrifying realization that the universe is much larger (a thousand trillion times, to be exact) than we thought

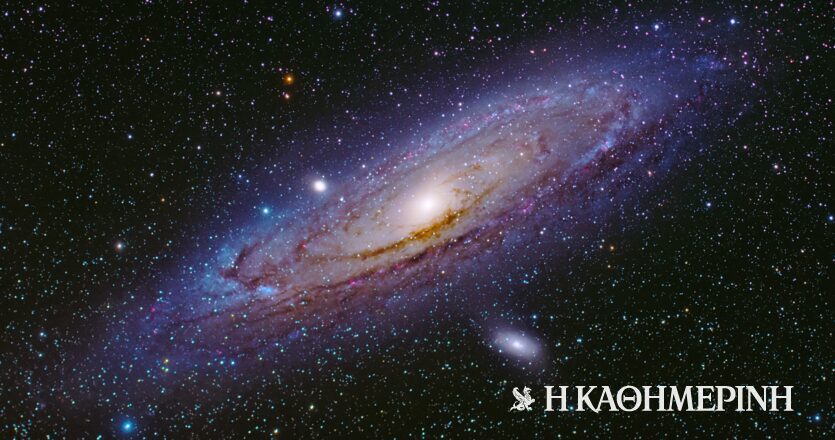

When, on New Year’s Day 1925, the young American astronomer Edwin Hubble announced his shocking discovery, the planet’s scientific community (and humanity as a whole) was shaken to its foundations. As Marcia Bartosac wrote characteristically in her book, “It was as if we were crammed into a square meter of the earth’s surface and suddenly realized that there were in fact oceans, unexplored continents, cities, villages, mountains, and deserts, stretching far beyond a little piece of land lying beneath our feet.” . And as if that wasn’t enough, four years later, Hubble made another shocking discovery: the universe was not static, but expanding. “Spacetime was moving,” Bartosak writes in her lyrical tone.

Awarded six times by the American Institute of Physics, her writing has been published in such iconic journals as National Geographic, Discover, Astronomy, Science, and MIT Technology Review, and she maintains a regular column in the Journal of Natural History. In addition, until recently, she was a professor in the graduate program in scientific writing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). But her writing is more impressive than her autobiography. However, one must read The Day We Discovered the Universe to feel her remarkable talent unfold in the adventures of science, while at the same time telling a story about the human soul and its intricate depths.

With her bright blue eyes, short red hair, warm voice, and a bright suburban Boston morning light illuminating her desk and books, Marcia Bartosac is as passionate and tender in our conversation as she is in the prose of her wonderful book.

One of the things that dominates “The Day We Discovered the Universe” is the historical context of time and the terrifying scientific progress – especially in the field of astronomy – that characterizes it. Can you talk to us about that?

Indeed, the 1920s saw some amazing steps forward at every level of science. All of this sudden big progress was happening because of a unique coincidence, a combination of limiting factors. It was a perfect storm.” The wealth generated by the great economic boom of the United States at the end of the nineteenth century led to private funding for scientific research and the use of new instruments—such as microscopes and telescopes—as well as new, more precise electronic instruments, which in turn helped give birth to new ideas and theories. This whole climate in particular in the field of astronomy was very lively.An example of this is the technology of telescopes at that time, which began to be made on the basis of mirrors, and no longer lenses, which made them stronger.Great industrialists such as Rockefeller or Carnegie helped with their donations to make all this happen Evolution, as the state did not yet have the mechanisms to do so.Of course, there were also a number of important scientists in this field, such as George Hill at the Mount Wilson Observatory, who had an uncanny ability to understand what was needed to move the field of astronomy forward. , ambitious visions like Hubble.

– How “American” is all this history and what has been going on in parallel in astronomical research on the other side of the Atlantic?

Research in gravitational wave astronomy is a new way to explore the universe not through electromagnetic radiation, but through space-time vibrations.

– Indeed, we can call this story “American”. It is the story of America’s “ripening”. In the last years of the nineteenth century, there was an alarming rise in the country’s GDP and a concentration of great wealth – that is, what has also happened in China over the past decade. At the same time, America had an ambition to bypass “mother” Europe, and wealthy businessmen with a social conscience helped in this. They provided the resources to build the best and largest telescope in the world. It was, you see, a matter of prestige, a way of “raising” the name of the country. At the same time, it made sense to leave Europe, which suffered from the First World War and got stuck in the slow procedures of government funding for scientific research.

One element that emerges in the story your book tells is the emotional personal ambition of its protagonists. Does the ego hinder progress or does human vanity fuel it?

– They both happen. My book shows how the great astronomer Harlow Shapley, the “golden boy” of astronomy in the 1920s, realized there were other galaxies, but didn’t really expand his method. His ego prevented him from seeing more. However, in the case of Hubble, his grandiose ambition to make great discoveries (and of course his remarkable sensitivity) propelled him forward. Spiral nebula research wasn’t exactly popular at the time, but Hubble bet on it. and won.

Do we expect an era of great discoveries to come again?

– Yes, and it did come with the James Webb Space Telescope, which is worth noting as a direct descendant of basic cosmology started by Hubble, who said for the first time that there are galaxies other than our own and a vast universe out there to be discovered. This telescope is the ultimate tool for taking the big ‘next step’. I think that’s how we’re going to learn (and actually learn) about creating the first stars. We’ll be able to see it “light up” and this has been something of a “holy grail” for astronomers for decades. There’s also all this new research going on in gravitational wave astronomy, a new way of exploring the universe not through electromagnetic radiation, but through the vibrations of spacetime. Thus, we may understand how gravity – which describes the universe as a whole – works, but also quantum mechanics – which describes the microscopic world as a whole. We may be able to see how these two voids can combine, which is what happens in black holes – where gravitational wave astronomy sets its sights on. All this research will take us back to the moment of creation of the universe, and this will be a great and wonderful moment for our science and our civilization. Imagine that we are now talking about the possibility of other universes within a “multiverse”. Ah, yes, I am sure that in the coming years and decades we should expect many more surprises about the universe. And you know what? We always say the same thing, “Now we know everything,” but in the end change always comes. We always think we have the “ultimate” model of the universe, and then something new comes along that changes everything. It is simply an ongoing pattern in humanity’s unstoppable march forward. We have to get used to this idea and finally become more humble.

Marcia Bartosiak, “The Day We Discovered the Universe.” Themistokis Halikias, published by Moment, p.556.

“Total alcohol fanatic. Coffee junkie. Amateur twitter evangelist. Wannabe zombie enthusiast.”

More Stories

The first cast for the show has been announced

Silent Hill 2 remake: Konami changed the face of the hero (photo)

Britain: An 11-year-old boy discovered fossils of the largest marine reptile ever to exist