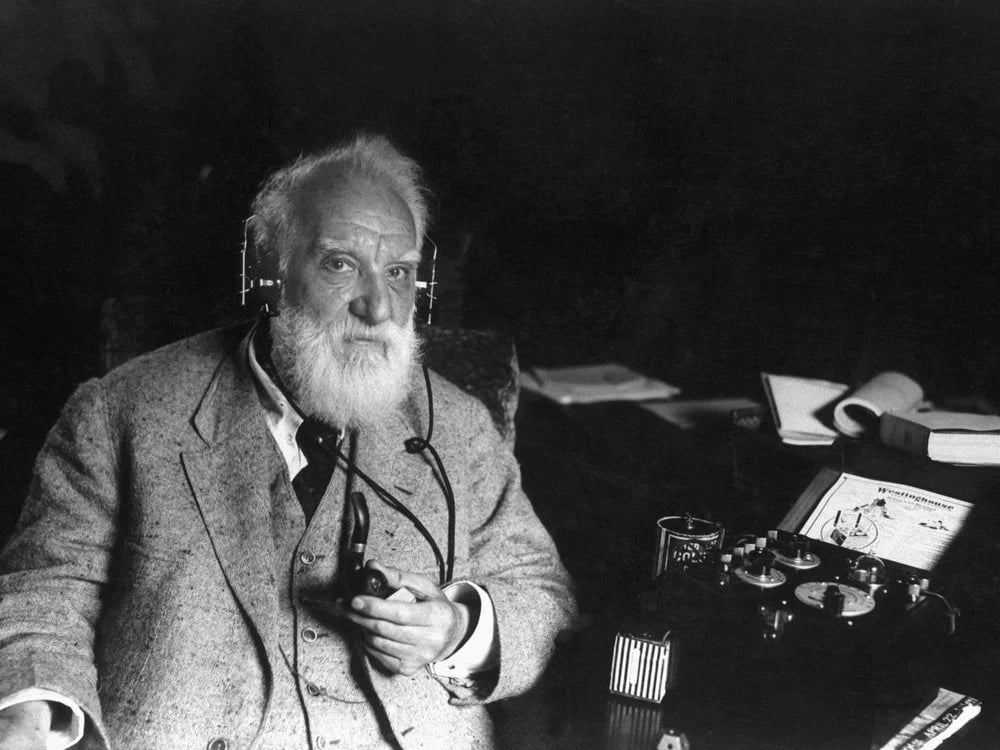

But it is important Discovery It came to light in 2013 when Smithsonian researchers discovered a previously “unreproducible” recording of the world on a wax and cardboard disc.

Bill declared, “Listen to my voice.” For the first time since his death in 1922, the world was finally able to hear his words.

Now, the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History has announced a new project: the recovery of hundreds of never-before-heard recordings of Bell and his colleagues between 1881 and 1892. The recording took place at Washington, D.C.’s Volta Laboratory. and Bell’s property in Baddick, Nova Scotia. In fact, these are some of the world’s first recordings.

“During the three-year period of this remarkable project, A History of Hearing: Recovering Sound from the Experimental Recordings of Alexander Graham Bell, we will be preserving and giving access to nearly 300 recordings in the Museum’s collections from more than a century ago. For the first time, said Anthea Hartge, Director of the Elizabeth Macmillan Museum. , in a statement, said the new initiative would begin in the fall.

Born in Scotland in 1847, Bell is best known as the inventor of the telephone. He patented his methods on March 7, 1876. A few days later, he made his first phone call to his laboratory assistant: “Mr. Watson, come here. I want to see you.”

In recent years, researchers have already recovered voice from 20 experimental recordings at Volta Lab, including the only documented recordings of Bell’s voice. The new program will focus on restoring the rest of the group.

Cardboard and wax tablets that Bell and his colleagues created—which the research team will translate—were once considered “dumb things,” Carlene Stevens, curator of the National Museum of American History, told Charlotte Gray of the Smithsonian in 2013. He wondered “if we would ever know what was in it”, as the details of Bell’s attempts to reproduce it were lost to history.

But thanks to the hard work of experts from the museum, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and the Library of Congress, new technology has been developed to listen to the recordings.

The team uses computers to create a digital scan of the grooves of the wax disc, removing any scratches or damage that might hinder recovery efforts. The program then follows a virtual stylus moving over the grooves of the virtual disc, playing the audio as a new digital file. The result: unlocking a sound that’s been elusive for over a century.

-

17

“Total alcohol fanatic. Coffee junkie. Amateur twitter evangelist. Wannabe zombie enthusiast.”

More Stories

After 14 years, Apple will do the unheard of on iPads

NASA: Stunning images of lava lakes and mountains on Jupiter's moon Io

On May 7, the new iPads from Apple will be presented – Apple